The institution we know as Bentley University began quite humbly as a school of accounting and finance. Its founder — Harry Clark Bentley — was one of America’s foremost authorities on accounting practice. His teaching skills were just as formidable. His students at Boston University, learning their instructor was soon to depart, pressed Mr. Bentley to open his own school so they could continue studying with him. That’s how it all started.

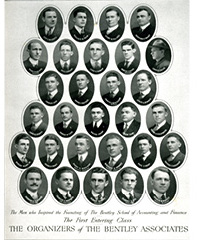

The first class, a group of 30 men, met on February 26, 1917, in the unremarkable Huntington Chambers building at 30 Huntington Avenue in Boston. There, Mr. Bentley taught classes three evenings a week plus Saturday morning. He had picked a promising time to enter the academic business. The U.S. government had implemented a federal income tax just a few years earlier, and the newly created Federal Reserve Board started to require uniform financial reports from companies. Such actions created a business boom for accountants.

The first class, a group of 30 men, met on February 26, 1917, in the unremarkable Huntington Chambers building at 30 Huntington Avenue in Boston. There, Mr. Bentley taught classes three evenings a week plus Saturday morning. He had picked a promising time to enter the academic business. The U.S. government had implemented a federal income tax just a few years earlier, and the newly created Federal Reserve Board started to require uniform financial reports from companies. Such actions created a business boom for accountants.

There were, at the time, a number of small, privately owned business schools in Boston. So the arrival of the Bentley School — a for-profit vocational institution that offered certificates and diplomas rather than degrees — did not make any ripples in established academic circles. Like other small schools of the day, Bentley had a more modest and focused mission than the larger, older colleges and universities in the area. Mr. Bentley sought to educate the next generation of accountants.

First-Generation Dreams

Early students at Bentley were typically older than those attending four-year institutions. Many came from Boston-area working-class families and therefore, needed jobs to pay their tuition. They were, in most cases, the first of their family to pursue any sort of post-secondary education.

From the start, and through its first few decades, Bentley focused on teaching students the information they needed to succeed in the accounting profession and to pass the state’s Certified Public Accountant (CPA) exam.

Admission in those early years was based primarily on a student’s ability to pay. But that pragmatism didn’t compromise Mr. Bentley’s commitment to delivering a rigorous education. As he liked to put it: “We teach like hell from bell to bell.”

Mr. Bentley had other aspirations as well. One was changing perceptions of accounting, uplifting the field from what some saw as menial bookkeeping to a genuine profession. Accordingly, he often counseled students on the grooming and social graces needed for the business world.

Opening Classrooms

The school was designed to admit only men. Given the biases of the times, professions open to women were often viewed poorly by the general public. Mr. Bentley took note and was reluctant to see the same happen for accounting.

The times brought changes to the young institution, however. The United States entered World War I just months after the Bentley School opened. As millions of men nationwide went off to fight, Mr. Bentley saw student enrollment dwindle precipitously. The school faced this first major hurdle with a willingness to adapt that has become a hallmark. Mr. Bentley decided to admit women to stay afloat.

The end of World War I would also mean the end of female students at Bentley — at least temporarily. Still, the school retained a more liberal stance on admissions than most others of the era. Mr. Bentley, a progressive Republican in the tradition of Theodore Roosevelt, opened up his growing classrooms to ethnic, racial and religious minorities, who faced either limited acceptance or outright rejection by established academia of that time.

Such stories illustrate the complex environment in which Mr. Bentley and the school operated at the start. Moreover, they speak to who Mr. Bentley was: a deeply ethical and generous person. He was known to lend money to students, particularly during the Great Depression, so they could finish their studies. But he also could be very hard-headed and determined.

These characteristics helped the Bentley School survive through war and economic hardship. Time and again, Mr. Bentley and his team of academics exercised tremendous leadership against such challenges. They made smart decisions that kept this school growing, even as other small private schools closed. In 1942, for example, as another large number of young men went off to war, Mr. Bentley moved again to admit women; the policy that remained in effect thereafter.

Ambitious Aims

The Bentley School faced new challenges in the wake of World War II. The federal government and individual states became major players in post-secondary education, paying for veterans to attend college and funding expansion of community colleges and state universities. The hugely popular G.I. Bill and growing public interest in post-secondary education spiked enrollment at Bentley — but also at competing schools.

Mr. Bentley came to believe that, to flourish, his school must award four-year degrees rather than diplomas and certificates. He noted that a college degree was often a prerequisite to receive an officer’s commission in the U.S. military, for example, while 120 semester hours of college credit was required to take the CPA exam in New York (as it soon would be in other states). He saw, too, how his students were ineligible for educational deferments from the Selective Service System and could be drafted to fight at any time.

These factors inspired a critical move in 1948. Mr. Bentley converted the private for-profit school into a self-governing nonprofit institution with a Board of Trustees. And the board’s first task: transform the Bentley School into a degree-granting college.

The work involved redressing many non-collegial characteristics of Bentley.. These included an extremely high student-to-teacher ratio, an absence of small and even medium-size classes, an emphasis on teaching that kept teachers from doing research, and an accountant-heavy Board of Trustees that lacked professional diversity. The school also had a shortage of faculty with master’s and doctoral degrees.

These obstacles discouraged the trustees. But Mr. Bentley persevered and worked hard to win others to the cause. As he wrote In a February 1950 letter to the board’s executive committee: “We should not assume the smug attitude that because the school has done well thus far it can continue to do equally well without regard to the consequences of future developments in the field of education.”

Mr. Bentley, by then in his 70s and moving toward retirement, identified his successor’s biggest priority as overseeing Bentley’s evolution into a college.

Graduating to a College

Maurice M. Lindsay assumed the role of president in 1953. A vice president who had joined Bentley in 1920 as an accounting instructor, he steered a steady course. The school retained its focus on training accountants, and continued to draw mostly working-class white men from the Boston area who could afford its exceptionally low tuition ($475 a year for day students in 1958). Bentley remained in Boston, even as rising enrollment fueled expansion in and around its headquarters at 921 Boylston Street.

Maurice M. Lindsay assumed the role of president in 1953. A vice president who had joined Bentley in 1920 as an accounting instructor, he steered a steady course. The school retained its focus on training accountants, and continued to draw mostly working-class white men from the Boston area who could afford its exceptionally low tuition ($475 a year for day students in 1958). Bentley remained in Boston, even as rising enrollment fueled expansion in and around its headquarters at 921 Boylston Street.

Among other accomplishments, President Lindsay strengthened Bentley’s ties to alumni, and prompted the school to launch its first capital campaign, which helped enlarge the footprint of the Boston campus. Notable milestones also included establishing the first cafeteria, first respectable library, first non-rented dormitory, first scholarships, first student newspaper and alumni magazine, first standing faculty committees, and first ranking system for faculty. All were important steps toward gaining collegiate status.

In 1961, the school received authority to grant a four-year degree, specifically the Bachelor of Science in Accounting. The Bentley College of Accounting and Finance was open for business.

Looking Outward

Becoming a college set the stage for dramatic changes throughout the 1960s. Under its third president, Thomas L. Morison, Bentley added a liberal arts program and an athletics program, and expanded the ranks of faculty and administrative staff. It instituted a system of faculty tenure and gained accreditation by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges in 1966.

There was significant growth in student enrollment during the 1960s. Bentley doubled day school enrollment over the course of the decade, thanks in part to the baby boomers who reached college age. Enrollment was 1,894 students in the 1969-1970 academic year. The faculty expanded accordingly, reaching 109 professors by 1969.

To accommodate such growth and position Bentley for the future, college leaders determined the college could no longer get by with its cramped facilities in Boston. They considered other locations in the city as well as in several nearby communities. Acknowledging that a move to the suburbs would be risky, they nonetheless took action upon seeing a prime 100-acre suburban property with stunning views. Bentley bought the land in 1962 and solidified plans to build a campus in Waltham, within the growing Route 128 industrial and commercial corridor.

President Morison and Dean of Faculty Rae Anderson wrote of the plans in 1965: “The campus that will rise on the academic plateau now being created on the crest of the great hill of the North Campus has been articulated in New England colonial architecture of the Georgian period. The style of architecture selected was not chosen by chance or happenstance. As an institution with deep roots in New England, Bentley College chose a style that would take full advantage of the spectacular location and capitalize upon the natural beauty of the surroundings, in full harmony with our New England heritage. The goal is to create something of beauty — beauty of a lasting character. Hence, the decision to forego contemporary design of an ephemeral nature.”

President Morison and Dean of Faculty Rae Anderson wrote of the plans in 1965: “The campus that will rise on the academic plateau now being created on the crest of the great hill of the North Campus has been articulated in New England colonial architecture of the Georgian period. The style of architecture selected was not chosen by chance or happenstance. As an institution with deep roots in New England, Bentley College chose a style that would take full advantage of the spectacular location and capitalize upon the natural beauty of the surroundings, in full harmony with our New England heritage. The goal is to create something of beauty — beauty of a lasting character. Hence, the decision to forego contemporary design of an ephemeral nature.”

Push and Pull

Not everyone was so entranced. Bentley had long drawn most of its students from Boston and nearby neighborhoods; many chose the school because it offered a solid education they could reach by public transit. Would students follow Bentley west? The Waltham site was large enough to meet the school’s needs, but its location in a city then on the downswing inspired concern. Some trustees and other leaders saw a threat to the well-being of the institution.

Robert O’Connor, a longtime dean of Bentley’s evening division, spoke for many in calling the move to Waltham “a huge leap of faith.”

The change of venue signaled the final transition from a city night school to a residential day college. Leaders had to contend with a range of new administrative requirements, from maintaining campus security to caring for 12 new buildings and expansive grounds. It was a whole new ballgame and victory not assured.

Indeed, Bentley entered the 1970s with a dimmer outlook than it had 10 years earlier. Enrollment dipped, expenses outstripped income and layoffs ensued.

Holding Firm

Yet college leaders, under the direction of Gregory H. Adamian, held firm to their vision. Moreover, President Adamian brought new rigor and vitality to the institution. Over his presidency, from 1970 to 1991, Bentley would not only cement its reputation as a center of excellence for accounting education, it would emerge as a strong, well-rounded establishment.

In 1971, the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education authorized Bentley to offer a full range of Bachelor of Science and Bachelor of Arts degrees. With that, the Bentley College of Accounting and Finance became, simply, Bentley College. The school’s graduate program started in 1973, offering Master of Science degrees in accounting and taxation. Academic initiatives included creating the Center for Business Ethics  (1976) and extracurricular options expanded with the opening of the Dana Athletic Center (1973).

(1976) and extracurricular options expanded with the opening of the Dana Athletic Center (1973).

The wisdom of moving from Boston was becoming clearer all the time. Waltham and other suburbs saw an explosion of business growth that brought a new class of companies to the state and the country. Boston-based industrial firms like United Shoe Machinery Corporation and United Fruit Company, which once hired scores of Bentley graduates, were falling victim to changing times. Businesses focusing on technology emerged in their wake. Bentley College officials took steps across the institution to ensure that students were prepared for this new economic era.

Playing on a National Stage

President Adamian oversaw Bentley’s transformation from a regional accounting school to an institution recognized nationally for innovative business education. The number of faculty jumped from 42 to 350 during his tenure, and full- and part-time enrollment doubled. Plans called for recruiting more women and more students from outside Massachusetts.

Moreover, academic offerings expanded from a single program in accounting to undergraduate degrees in 11 business and liberal arts disciplines. The school’s endowment benefited as well, going from $385,000 in 1970 to $60 million in 1991. The years saw construction of 27 buildings, including residence halls and academic, administrative and athletic facilities.

The school’s long commitment to ready students for the professional world surged forward. In fall 1984, Bentley gave all first-year students portable computers. It would shortly become the first college to require laptop computers for all students.

Ebb and Flow

Growth slowed during the last decade of the 20th century. Student enrollment stalled or decreased in the midst of economic recession and declining interest in business studies. There were staff layoffs and campus construction came to a halt.

Still, Bentley leaders stayed focused on the future. Joseph M. Cronin, president from 1991 to 1997, worked with students, faculty, administration and alumni on a new strategic plan. In particular, it called for globalizing a Bentley education. Students gained opportunities to study abroad and more international students arrived to study in Waltham. President Cronin was instrumental in fostering a spirit of diversity and acceptance on campus, particularly through outreach to gay and lesbian students.

The school welcomed its sixth president, Joseph G. Morone, in 1997. He led efforts to build on longtime strengths across the college, and increased funds for research, teaching and curriculum development. There were significant improvements to campus infrastructure and new facilities that positioned Bentley as “the business school for the information age.” Construction boomed again, with the opening of the Smith Center for Academic Technology and the Student Center as well as a $13 million renovation of the library. Campus aesthetics improved with the addition of a Greenspace, made possible by repurposing parking lots and acquiring 33 acres of nearby property.

The school welcomed its sixth president, Joseph G. Morone, in 1997. He led efforts to build on longtime strengths across the college, and increased funds for research, teaching and curriculum development. There were significant improvements to campus infrastructure and new facilities that positioned Bentley as “the business school for the information age.” Construction boomed again, with the opening of the Smith Center for Academic Technology and the Student Center as well as a $13 million renovation of the library. Campus aesthetics improved with the addition of a Greenspace, made possible by repurposing parking lots and acquiring 33 acres of nearby property.

Becoming a University

The expansion of programs, faculty and research capacity under President Morone helped Bentley achieve another ambitious goal: university status. The school met the chief criterion for the elevated position in 2005, when Massachusetts granted authority to award PhDs in business and accountancy. Three years later, the state approved Bentley’s petition to call itself a university.

In 2007, the school named its first female president: Gloria Cordes Larson. Milestones during her tenure include launching a distinctive 11-month MBA program, establishing the Center for Women and Business, and facilitating research on how well colleges and universities are preparing students for the 21st century workplace. The school’s visibility and reputation have grown apace. For example, Bentley is one of only three U.S. educational institutions to earn accreditation by the European Quality Improvement System, which benchmarks quality in management and business education. An annual ranking by Bloomberg BusinessWeek lists Bentley as one of the Top 10 business schools nationwide for 2016.

Now, the centennial year is upon us. Mr. Bentley would certainly be astonished at what his school has become. In his time, he had questioned the need for his students to study much other than accounting. But he did see the wisdom of adapting to changing times. (Witness his push for teaching students how to use the adding machine and other new technologies of the day.) Moreover, as a man who appreciated opera and other fine arts, he understood the value of a broadened perspective. As he often told students: “I can teach you everything about accounting, but accounting isn’t everything.”

At age 100, the university is striving to deliver on the “everything” that Mr. Bentley envisioned.

Associate Professor of History Cliff Putney is writing a history of Bentley.