Viruses and Vaccines

Professor Zoë Wagner explains the science behind COVID-19

It seems hard to imagine now, when virtually every aspect of our daily lives has been disrupted by COVID-19, but just four months ago, few people had ever heard the term “coronavirus.” What began as a cluster of mysterious respiratory illnesses in Wuhan, China has become a global pandemic that, to date, has sickened more than 1.6 million people — and claimed the lives of nearly 100,000 — in almost every nation.

In a streamed presentation, Viruses and Vaccines: Your Questions Answered, Natural and Applied Sciences Lecturer Zoë Wagner explained why COVID-19 has proven so deadly, and what we can do to keep ourselves and our loved ones safe and healthy. The event, part of a series from the university’s Office of Alumni and Family Engagement, drew participants from seven countries.

Missed Professor Wagner’s Webinar?

A pharmaceutical scientist and bioengineer, Wagner has firsthand experience researching treatments for debilitating health conditions: As a graduate student at the University of Southern California, she explored how pH-responsive protein nanoparticles can help eradicate cancerous tumors. In her online presentation, Wagner provided answers to common coronavirus questions, including:

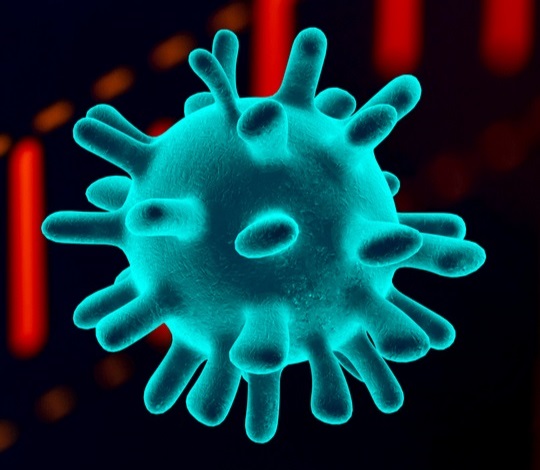

distinctive shape, which features a

halo, or corona, of spiky viral proteins.

- What is a coronavirus? A virus is a small infectious agent that needs a living host — animal, human, plant or bacteria — to survive. A coronavirus, Wagner noted, is a specific virus named for its shape: “It’s completely surrounded by a halo, or corona, of spiky viral viral proteins.”

- What happens if I’m infected? As a respiratory disease, COVID-19's primary target is the lungs. More specifically, it attacks the alveoli, “the tiny little air sacs at the ends of our lungs where oxygen exchange is happening,” Wagner said. As the virus attacks healthy cells, the alveoli begin filling with fluid, causing pneumonia. Most people who develop COVID-19 will have healthy immune systems strong enough to fight off the infection. However, for older patients or those with underlying medical issues such as diabetes, heart disease, and auto-immune conditions, the lungs become so filled with fluid that it’s impossible to breathe on their own. That’s when a ventilator is introduced, to mechanically move pressurized air in and out of the lungs. However, “there’s still a biological limit our lungs are able to withstand,” Wagner said. Even with ventilator support, critically ill patients are likely to succumb to acute respiratory distress and multiple-organ failure.

- How fatal is COVID-19? One measure of the fatality rate for a specific disease, Wagner explained, is found by dividing the total number of deaths by the total number of diagnosed cases. While this seems straightforward, it's anything but due to the global disparity in coronavirus testing protocols: Most nations, including America, are testing only those patients with the most severe symptoms. Because those with milder cases aren’t always tested, the fatality rate can be inaccurate. Currently, Wagner says, the fatality rate is roughly 6.1 percent worldwide, and about 3.6 percent in the U.S.; however, these numbers are “almost certainly going to change” as testing rates improve.

How Politics Impeded America’s Response to COVID-19

- Which treatment options are available? Because COVID-19 is new to humans, we haven’t built up an immunity to it. As a result, there are no definitive treatment guidelines. For the short term, the medical community is looking to existing drugs to treat coronavirus symptoms. Wagner noted that while several medicines — most notably hydroxychloroquine, an antimalaria drug, and remdesivir, an Ebola treatment — have shown limited success, "frankly, there’s just not enough information available yet.” For the long term, researchers are racing to develop a vaccine. One Massachusetts-based company recently announced the start of clinical (human) trials for its version, but Wagner cautioned it will still take time — at least 12 to 18 months — to produce an effective vaccine: “We cannot sacrifice safety for speed.”

- I don’t have the virus. What can I do? Despite the severity of symptoms and obstacles to treatment, Wagner struck a hopeful note by reminding webinar participants that each of us has the power to limit the spread of COVID-19. “Our job right now is to practice physical distancing,” she said, while also maintaining our social connections, “which are so important for our mental health and well-being.” In other words: “Now would be a great time to practice kindness and reach out to friends, family and colleagues.”