The Power of Perceptions

Even as a little girl, Mounia Ziat had big dreams.

The associate professor of Experience Design (UX) remembers a time in primary school when her parents asked her what she wanted to be when she grew up. She replied without hesitation, “Engineer of everything.” Although her parents laughed indulgently, Ziat — a self-described “shy kid who used to stutter and was terrible at sports,” loved math, science and drawing, and counted Leonardo da Vinci among her childhood idols — wasn’t discouraged. “I couldn’t imagine having to choose just one thing,” she says. “I wanted to do it all.”

In many ways, she has. Today, Ziat is an internationally recognized scientist, scholar and innovator in the field of haptic technology, or human-computer interaction mediated through touch. Like da Vinci himself, she’s a proud polymath, with degrees in electrical engineering, graphic design and cognitive science gleaned through studies undertaken on three different continents. She fluently speaks Arabic, French and English, and is learning Mandarin; she also takes advanced art classes and is learning to play the guqin, an ancient stringed instrument revered by Chinese sages and scholars, including Confucius.

RELATED: Prof. Ziat awarded Google grant to support Deafblind community

While Ziat’s achievements are impressive by any definition, they’re even more remarkable given the challenges she faced growing up in Algeria, a former French colony and Africa’s largest country. In 1991, tensions between the Algerian government and rebel Islamist groups developed into armed conflict, unleashing violence that would endure for more than a decade. It was an unsettling time for many, and Ziat — who attended the University of Science and Technology in Setif, Algeria and, later, the acclaimed École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) in the capital city of Algiers during these years — found refuge in academia.

Her art studies provided the foundation for her later interest in tactile technology. “I took a class about the philosophy and psychology of art that brought me back to my engineering roots,” Ziat says. “I became interested in the idea of human-centered design, how devices designed for humans need to be based on a thorough understanding of humans and our intellectual and emotional needs.”

After graduating from art school, she immediately enrolled in a graduate program in cognitive science at The University of Technology of Compiegne in northern France. A field of study that emerged in the 1950s and ’60s, cognitive science draws upon knowledge from multiple disciplines — including linguistics, neuroscience, biology, psychology, philosophy and computer science — to understand how humans collect and process information.

Ziat found the connection between cognition and sensory perception particularly compelling. As she explains, “We are multimodal beings,” and as such rely on a multitude of sensory stimuli for knowledge acquisition. Whether that information is visual (sight), auditory (hearing), olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste) or haptic (touch), it must be processed by nerve receptors in our brains before we can interpret our surroundings. As the human brain contains an estimated 86 billion neurons, or nerve cells, interconnected via approximately 100 trillion synapses, or neural pathways, precisely how the brain interprets sensory stimuli has remained a mystery — one that scientists like Ziat are eager to solve. She decided to focus on haptic perception, she says, because “Skin is the human body’s largest organ, and our sense of touch is what connects us to our physical world.”

Currently, Ziat is working on two separate haptic research projects. The first is a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) project with Pison, a Boston-based manufacturer of wearable technology, and the U.S. Air Force. Known as MINOTAUR (Minimalist Operator Tactile Alerting for Universal Reconnaissance), the project supports the development of gesture-control wristbands for military use and is funded by grants totaling $750,000.

MINOTAUR explores the use of Pison wristbands to provide situational and directional information to U.S. soldiers, Ziat explains. For example, vibration signals could help military personnel navigate in situations where visibility is limited: “A vibration on the left or right side of the band would indicate I need to go in the corresponding direction.” Variation in the frequency and intensity of vibrations could also be used to differentiate threat levels, such as the presence of enemy combatants, or proximity to predetermined targets. Ziat and her team of research assistants — which includes current Bentley graduate student Abu Batjargal MSHFID ’23 — are responsible for designing and testing the haptic information systems Pison will demonstrate to the military sponsor.

Ziat’s second research project is underwritten by a $455,000 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and explores edge perception — or, more accurately, how our hands and fingertips interact with surfaces, edges and vibrations to identify objects. “Whenever we touch something, it generates tiny vibrations between the object and our skin,” she explains. “These vibrations are differentiated by the kind of touch we use — tapping or sliding our fingers across a surface, for example, or gripping something with our entire hand — and are received by mechanoreceptors, which are specialized nerve cells embedded in our skin.”

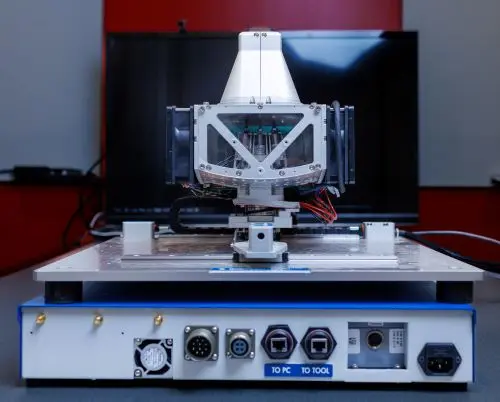

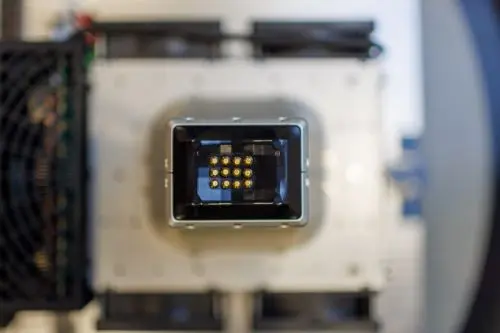

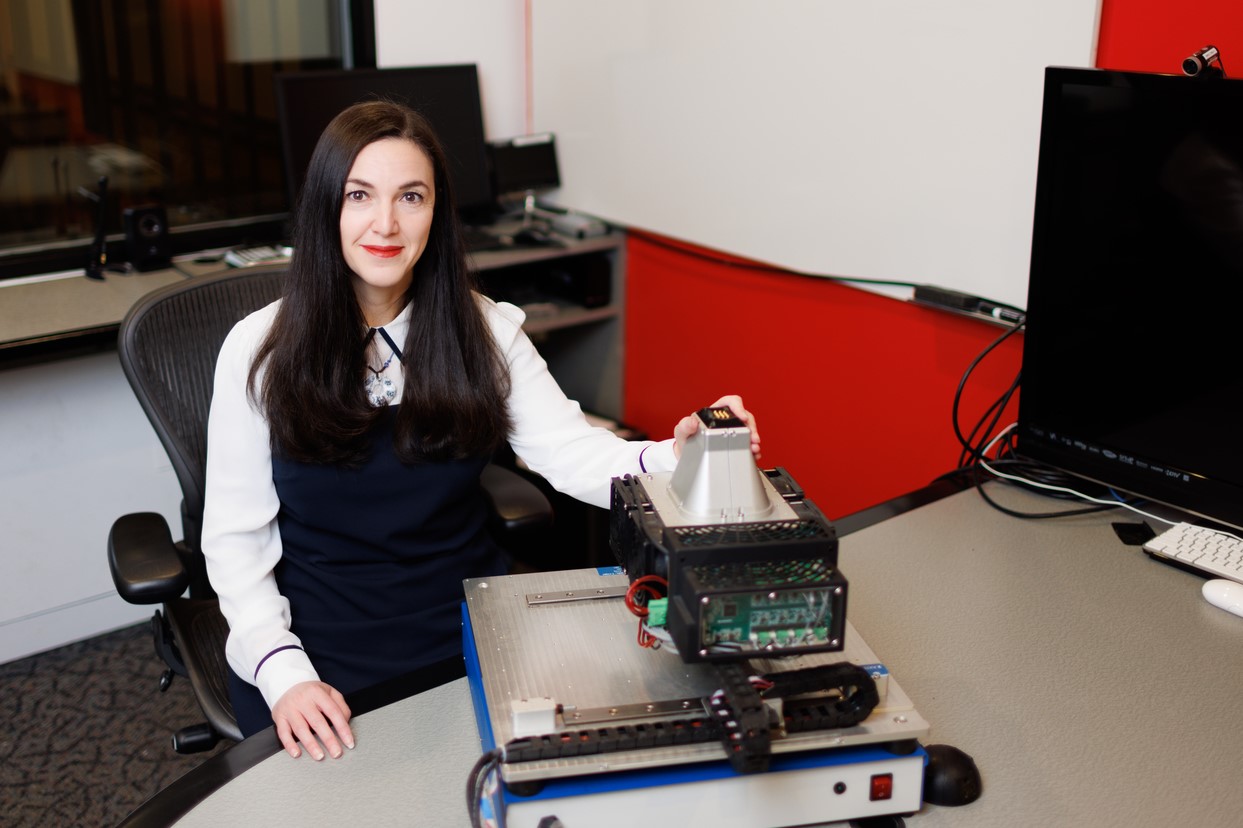

Using a tactile processing machine of her own design, Ziat and her research team will conduct experiments using computer-controlled stimuli with adult subjects. Her goals are to generate a more complete understanding of how different kinds of mechanoreceptors respond to objects’ edges and contours, and to explore if and to what extent other sensory systems, such as sight and sound, affect our ability to distinguish tactile sensations.

RELATED: Students use multisensory systems to solve real-world problems

Beyond advancing a general understanding of tactile stimuli and human cognition, Ziat’s study also has practical applications. “Haptics is an increasingly important area for technological innovation,” she explains, nothing that devices with haptic interfaces are currently used to teach people how to repair or maintain complex products, such as airplanes and heavy machinery. She’s particularly excited by the possibility that her research findings may be used to empower the visually challenged, much as Louis Braille did a century ago by developing a tactile system for reading and writing.

Indeed, the desire to improve people’s lives through science and technology is a fundamental reason why Ziat chose haptics as her field of primary study. To date, she’s adapted a tactile processing device for Deafblind children, explored the use of multimodal VR (virtual reality) experiences to ease the discomfort of medical patients receiving injections, affirmed the use of highway rumble strips to improve driver safety in inclement weather, and more.

This altruistic instinct, much like Ziat’s ambition to be “engineer of everything,” is also characteristic of her childhood. She recalls a promise she made as a teenager to her aging grandmother, who lamented the limitations of growing older: “I told her not to worry, that I would build a special robot just for her that would help her with the laundry, cooking, cleaning, whatever she needed. I even gave her a signed contract.”

It’s a sentiment that has sustained Ziat throughout her academic career: “I believe in the power of technology to help us create a better world.”