Design for Digital Habits

Published by Sydney Bee

Contributions by Jennifer Siegel and Amanda Mattson

Over the last three decades, the Internet has drastically accelerated the speed at which information can be accessed. The impact of ubiquitous digital products and services on our behavior spans deep and broad. From checking email on our phone every 15 minutes, to buying diapers without setting foot outside the home, to connecting families on Facetime—a plethora of apps on our devices have infiltrated our lives as “new habits.”

Sustaining Behavioral Changes in the Digital Age

Many of these behaviors are digitized versions of existing practices, such as shopping online instead of in physical stores, using an app to call an Uber instead of hailing a cab, or reading a book on a Kindle instead of purchasing a hard copy. These advancements allow us to perform familiar daily tasks faster, cheaper, and better.

Introducing a new behavior (or, in other words, developing unfamiliar habits) is much more challenging. Despite having more tools to exercise and learn new skills, there is limited evidence of the impact of Fitness Trackers, and research demonstrates lower retention rates in the online classroom as compared to traditional methods. What user experience elements can help in the successful adoption of a new habit?

Formation of Habits

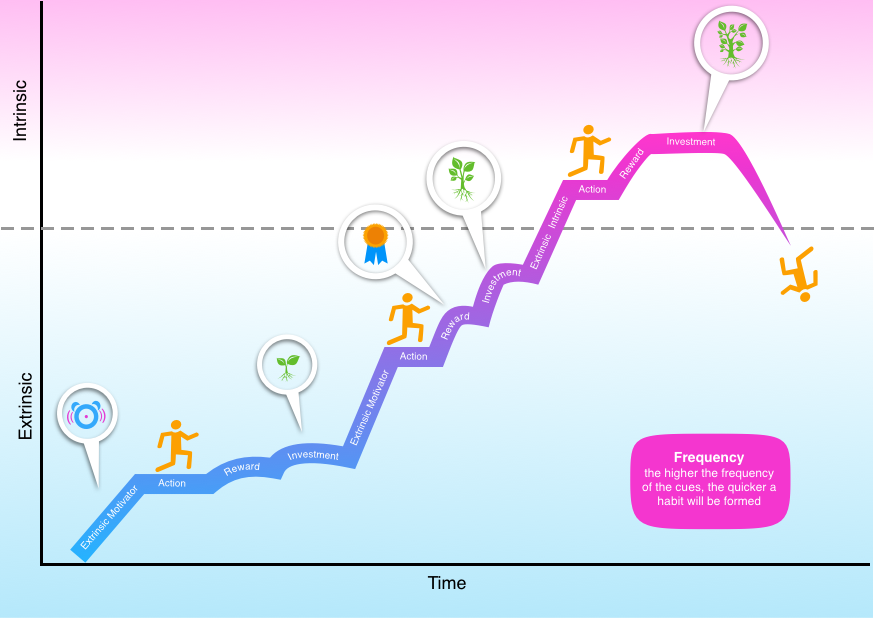

Thought leaders in habit formation (such as Nir Eyal, Charles Duhigg, and BJ Fogg) describe an iterative and progressive process for creating enduring behavioral change. For example, the Hooked model describes 4 stages: Trigger, Action, Reward, and Investment. For designers of digital habits, the key to manufacturing enduring behavioral change is not only designing an effective externaltrigger, but also translating the rewards into self-motivation, thereby creating strong internal triggers.

The key to manufacturing enduring behavioral change is not only designing an effective external trigger, but also translating the rewards into self-motivation, thereby creating strong internal triggers.

Existing habits are easy because they are an infallible part of a user’s workflow. These habits may be cued by a commonly seen object or the time of day. In the case of improving upon an existing habit such as “reading before bedtime,” where users are self-motivated avid readers, they can simply modify the external triggers in their workflow—trading a paper book on the nightstand for a Kindle and a charger. If the new added value of convenience outweighs the trouble of charging the device, the modified habit will be sustained. However, for users who are not already habitual readers, the new activity may fade eventually.

The habitual readers’ advantage is their internal triggers. The powerful self-motivation that springs us into action will reinforce the behavior over time. Specifically, internal triggers are our recollection of a reward—a positive experience associated with the external cues and nudges. For example, the thrill from reading a good novel, the calm before entering a deep sleep. These rewards motivate the users to repeat their actions.

Reading a novel delivers instant gratification, other habits might take more time to generate emotionally motivating rewards. For example, a course certificate may remind students of their accomplishments, fill them with confidence and ambition to tackle the next course—but the student must adhere to weeks and months of diligent studying. Before the reward comes to fruition, the student must choose between watching the educational video and reading their favorite novel after a long day. The section below will discuss how to design for these internal triggers.

Designing for Irrationalities

Along the various stages and touch points of habit formation, common biases can deplete intrinsic motivation or lead users to abandon their behavior change. The following key behavior, psychology, and usability concepts can help UX researchers and designers avoid these pitfalls.

-

Availability: Plant frequent & memorable triggers

-

Cognitive Load: Reduce the barrier for entry

-

Myopia: Turn long-term goals into short-term rewards

-

Loss Aversion: Re-frame gains and losses into commitments

- Certainty: Remove doubts by building confidence and offering evidence

AVAILABILITY: PLANT FREQUENT & MEMORABLE TRIGGERS.

In order to inspire an immediate action, a trigger must draw from memories of a rewarding experience. Due to the ease of recall, emotions in the recent past are more consequential, credible, and motivating. Daily habits that offer joy, stimulation, and relaxation often rise to the surface of our memory (i.e. playing a mobile game while waiting for the bus, or having a glass of wine in the evening). Without available memories to draw from, the willpower of a user is quickly depleted, and the habit is abandoned before any positive outcomes and feelings can be formed. For example, entering calories after a meal seems like a simple act and a low investment that can help a user reap the long-term rewards of better health. However, the lack of rewards in the short-term leaves users with a memory bank empty of positive triggers. This will ultimately lead the user to abandon the habit before his or her investment pays off.

COGNITIVE LOAD: REDUCE THE BARRIER FOR ENTRY.

Habits are recurrent, and often unconscious, behaviors that are learned through repetition. While triggers may prompt a user to engage in a behavior, he/she may still abandon the behavior if it is too difficult to perform or learn. Furthermore, a survey of previous experiments reveals that cognitive load increases risk aversion and impatience. When performing a difficult activity, users tend to avoid uncertainty and abandon their activity before they incur significant loss of time and energy. Consequently, user-friendly designs that incorporate short-term goals are particularly imperative for the risk-averse and restless user.

MYOPIA: TURN LONG TERM GOALS INTO SHORT TERM REWARDS.

The avoidance of a short-term investment in spite of potential long-term rewards often precludes us from exercising for weight loss, or logging back in to resume a free online course. Furthermore, users are increasingly surrounded by technologies that provide instant gratification, which creates an environment in which our willpower faces more competition than ever. As such, manufacturing short-term rewards is crucial to ensuring our memory bank is frequently replenished with positive self-motivating triggers to nudge us into action.

One solution is incorporating pseudo-rewards in the short-term to combat other instantly gratifying temptations. Social recognition after completing a rigorous exercise or a small dessert for following a strict diet can ensure that a user draws from an available reservoir of positive associations.

LOSS AVERSION: RE-FRAME GAINS AND LOSSES INTO COMMITMENTS.

Another psychological barrier that prevents us from making smart choices for long-term benefits is our fear of loss. Irrationally, losses loom larger than gains; the pain we feel from losing what we have, can overpower any foreseeable pleasure. This bias leads us to excessively minimize losses. When we skip the gym in the morning, the perceived benefits of additional sleep overshadow the missed endorphin rush we feel after exercising.

Loss aversion also manifests itself when we evaluate the potential outcomes of taking an actionagainst avoiding that action. As shown from the popular phrase “fear of missing out,” being excluded from a social experience triggers greater pain than the pleasure associated with socialization. In this example, framing an avoidance as a loss is more effective than painting a rosy picture of the benefits.

In designing a habit-forming experience, we can discourage users from abandoning an action by incorporating small losses. Such penalties combined with rewards can mimic the effect of a “commitment.” In the short-term, users are motivated to protect the rewards they have won and avoid the painful loss of progress. These incremental investments will eventually allow users to reap long-term benefits.

CERTAINTY: REMOVE DOUBTS BY BUILDING CONFIDENCE.

We factor in alternatives when we make a decision. Alternatives often seem more attractive especially when long-term benefits of a new habit are not guaranteed or quantified. Would watching an hour of an online education video really increase my career prospects? Am I really smart enough to master a new skill? Such doubts signal potential loss of time, energy, and money. The alternative of working the extra hour instead guarantees extra pay. In essence, we favor certain and positive outcomes when facing choices.

UX designers and researchers can reduce uncertainties by providing incentives to keep users on track. For example, Carnegie Mellon’s Open Learning Initiative currently offers courses through a platform that provides targeted progress feedback to students. Active engagements allow students to gain control of their performance and increase certainty of mastery.

Once users repeat actions, other factors encourage them to continue investing. According to Daniel Pink’s book, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, we are driven by autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Designing to highlight these intrinsic rewards, such as “leveling up” or creating social meaning can have a significant effect. A study of FitBit use amongst Emergency Medicine residents attributed peer pressure as a factor in continued usage. Testimonials and assistance that shortens the learning curve can improve users' confidence and certainty of payoff.

Image credit: Amanda Mattson

Closing the loop for good.

We navigate through danger and avoid risks by drawing from our memory. However, the same decision-making processes can lead to irrational choices that prevent us from acting in our best, long-term interest. Digital technology enables designers to address predictable biases in habit formation by delivering short-term rewards, re-framing uncertainties, reducing barriers, and encouraging investments in ourselves.

About the author:

S ydney Bee

ydney Bee

Sydney is a UX Consultant at the User Experience Center and is passionate about discovering and incorporating unique societal values, cultural subtleties, and human factors in the designs of user & customer experience. She has worked with a variety of multinational clients in the US, Australia, Europe, China, and Southeast Asia to apply design thinking in solving customer engagement challenges and expanding the global footprint of products and services. Her work spans across financial services, transportation, healthcare, energy, and software industries with a focus on identifying strategic opportunities and producing actionable recommendations for both the short and long term.

Contributions by:

Jennifer Siegel and Amanda Mattson are Research Associates at the User Experience Center and are currently pursuing a Master of Science in Human Factors in Information Design from Bentley University.

Let's start a conversation

Get in touch to learn more about Bentley UX consulting services and how we can help your organization.