How navigation assistance through GPS has changed our behavior

The mass adoption of GPS-enabled mobile devices has fundamentally changed the way we interact with our environments. Navigation applications, such as Waze, Apple Maps, Google Maps, & MapQuest, have earned our trust, and we rely on them in our daily routines:

Locate Basic Needs

We use navigation assistance to find places to eat and buy gas. In many circumstances, it has become more convenient to consult a navigation assistant than to stop and ask for recommendations or directions in person.

Save Time

Our devices help us find optimal routes and avoid traffic, minimizing the time we spend commuting and running errands.

Backbone to Disruptive Technologies

The unprecedented growth of ride-sharing services, such as Uber and Lyft, over the past decade, would not have been possible without reliable, easy-to-use navigation assistance.

Safety Net

The technology enables us to travel beyond familiar territory with a high level of confidence. It has become increasingly more difficult in recent years to become truly lost while driving.

Potential long-term consequences

At what point does a safety net become a crutch? To find out, let’s review the science. Research shows that there are two types of strategies we adopt to navigate new and unfamiliar environments. We adopt these strategies spontaneously, unconsciously, and regardless of whether we are navigating with or without assistance.

Response Strategies

- Involve memorizing and sticking to a route

- Provide little motivation to travel outside of the route

- We can quickly become lost if we veer from the memorized path

- A means to travel through an environment

Spatial Strategies

- Involve forming mental maps of a place

- Learn significant landmarks and how to navigate between them

- Memories and emotions associated with the landmarks

- A means to connect to an environment

Why it Matters

Spatial strategies are a more difficult form of learning than response strategies. Spatial strategies and the hippocampus are closely linked, a region of the brain associated with mental maps and long-term episodic memory, memories of autobiographical events. Exercising spatial strategies correlates with an increase in the size of the hippocampus. Interestingly, research shows that degradation of the hippocampus is an early indicator of Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, there may be a link between exercising the brain’s wayfinding skills and normal aging.

You might be questioning how all of this neuroscience talk relates to GPS navigation? Well, studies have shown that following turn-by-turn directions from a navigation assistant produce neural activity suggesting the use of response strategies. This means that following GPS instructions limits our ability to build mental maps of our environments. When following turn-by-turn directions, we are not learning much about our surroundings; we are not connecting to our surroundings. When we over-rely on navigation assistance, our brains are not getting exercise, and it is possible this may have long-term consequences. There is no standard measure to quantify what constitutes as over-reliance of GPS navigation. I define over-reliance as routinely engaging with the technology despite when it is not needed to reach a destination.

How design can help

Contextual Directions

The user experience of navigation assistant technologies is overdue for a redesign. One promising solution is contextual navigation, directions which refer to local landmarks. These types of instructions more closely replicate the directions humans give each other in conversation. For example, instead of saying, “turn left onto School Street,” a navigation assistant could say, “take the first left past the train station.” Research findings suggest that contextual navigation instructions are just as easy and safe to follow as traditional directions; furthermore, they do not hinder our ability to generate spatial maps. Contextual navigation helps users learn new landmarks and how to navigate between them. Instructions that more closely mimic the directions humans give each other are just as easy to follow and help us better connect to the places we navigate.

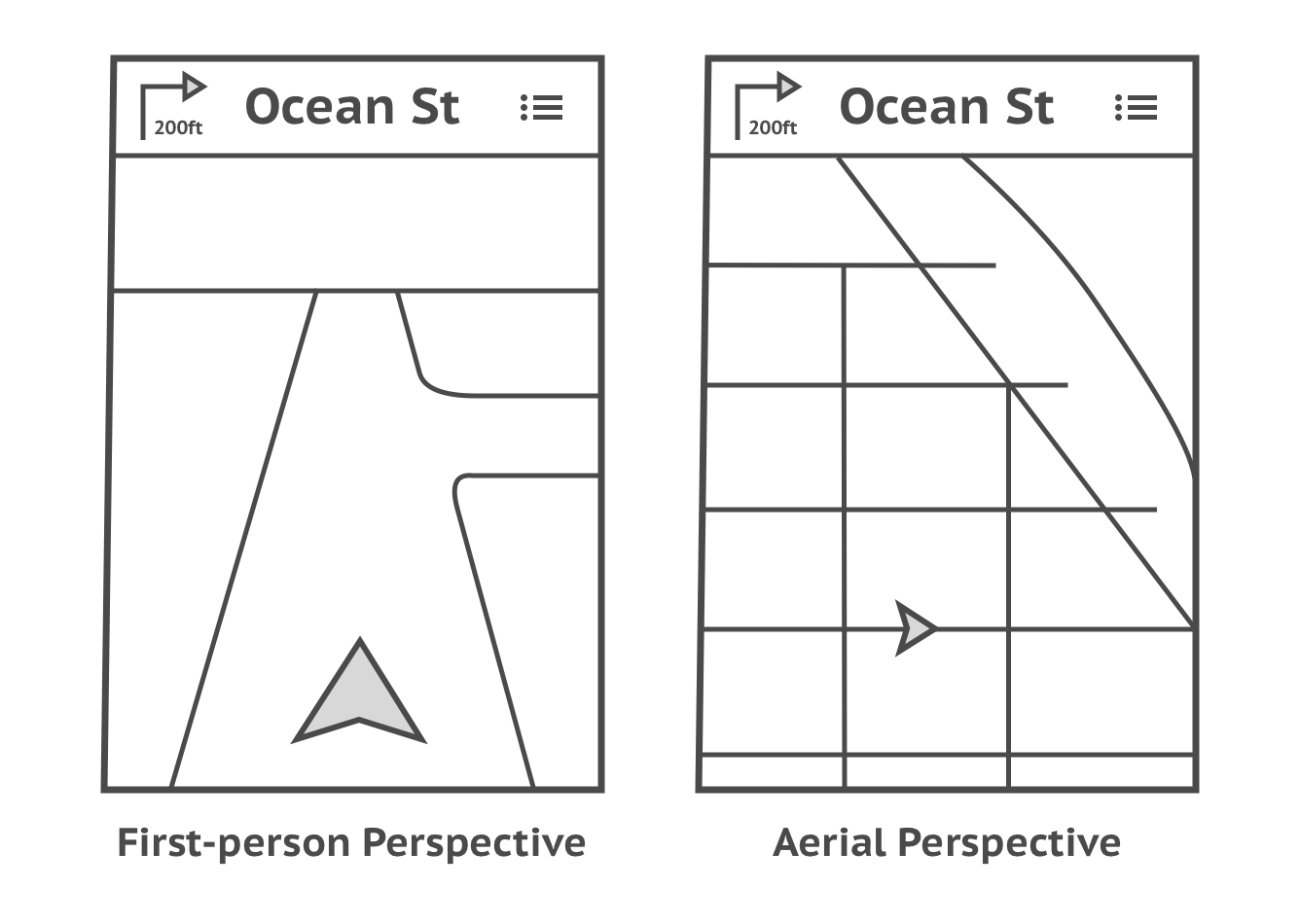

Optimized Visualizations

Another potential design solution is to change how we visualize maps. Research shows that displaying a map from a north-up, aerial perspective is conducive to learning new surroundings. First-person perspective interfaces are easier to follow; however, they hinder the user’s ability to learn new spaces. GPS applications could automatically switch between the two perspectives; this would maximize the gains of both perspectives. For example, when close to the next turn, the app could zoom in from an aerial view into a first-person perspective. Users would benefit from both the spatial learning advantage of aerial maps and the followability of first-person perspectives.

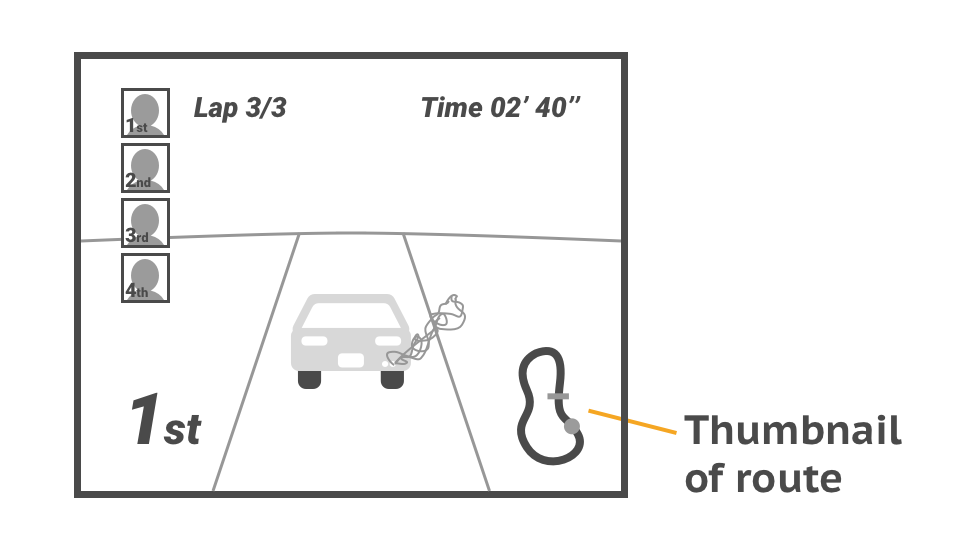

Route Thumbnails

GPS applications can incorporate small thumbnails showing the overall route and a small dot indicating where the user's current position on that route. Many video games use this strategy; however, I have yet to see it on a GPS navigation application. This design solution could be a helpful means to quickly and efficiently show users their current location in relation to their destination and origin.

Point to North

Lastly, GPS applications should always show users which way is north. Knowing which way is north will help users orient themselves and make better connections between various landmarks. Most of the maps we see are oriented north-up, and we understand landmarks as above, below, left, or right of each other on a 2-dimensional surface. Knowing which way is north helps users connect what they have seen on maps to the landscape in front of them.

Takeaways

It is becoming increasingly important to exercise our wayfinding skills, especially as navigation assistance becomes further integrated into our daily routines. Furthermore, new technologies such as autonomous vehicles will continue to alter our navigation behaviors. In the near future, a self-driving car might not require drivers to navigate at all. New technologies may improve upon public safety and reduce complexity in our lives; however, it is essential we view technology adoption as a tradeoff. To achieve an optimal user experience, it is not only important to maximize the gains of new technology, but it is also equally important to focus on the human skills a technology is replacing and to what degree the tradeoff is worthwhile.

Further Reading

Thorough Overview

Contextual Navigation

Relevant Opinion Piece

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/05/opinion/sunday/is-gps-all-in-our-head.html

Plasticity of the Brain

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/london-taxi-memory/

Peer-Reviewed References

Spatial VS Response Strategies

Bohbot, V. D., Lerch, J., Thorndycraft, B., Iaria, G., & Zijdenbos, A. P. (2007). Gray Matter Differences Correlate with Spontaneous Strategies in a Human Virtual Navigation Task. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(38), 10078–10083. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1763-07.2007

Contextual Navigation

Gramann, K., Hoepner, P., & Karrer-Gauss, K. (2017). Modified Navigation Instructions for Spatial Navigation Assistance Systems Lead to Incidental Spatial Learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00193

Turn by Turn Directions Do Not Activate Spatial Strategies

Javadi, A., Emo, B., Howard, L. R., Zisch, F. E., Yu, Y., Knight, R., . . . Spiers, H. J. (2017). Hippocampal and prefrontal processing of network topology to simulate the future. Nature Communications, 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14652

Neuroplasticity

Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S. J., & Frith, C. D. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(8), 4398–4403. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.070039597

Tradeoffs Between Map Visualizations

Münzer, S., Zimmer, H. D., & Baus, J. (2012). Navigation assistance: A trade-off between wayfinding support and configural learning support.. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18(1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026553

Darek is a Research Associate at the User Experience Center. Darek is an avid hiker, traveller, and all-around explorer. He loves to study maps of both familiar and unfamiliar places.

Darek is currently pursuing a Master of Science degree in Human Factors in Information Design from Bentley University. Prior to joining the UXC, Darek was a Graphic Artist at L.L. Bean in Portland, Maine. Darek holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree from Montserrat College of Art.

Let's start a conversation

Get in touch to learn more about Bentley UX consulting services and how we can help your organization.